Incomplete Prospectus for the Old Ways Museum on the Falling Water Farm

(The OWM on the FWF)

(rhymes with "home on the roof")

INTRODUCTION

While my mother, Barbara Camp Antonson, was still alive, I once asked her what she intended to do with all the primitive, farm-related stuff that she had accumulated during her lifetime. I believe this was at a point when her four other children and myself were involved in changing her residence from Concord, New Hampshire (where she had lived for 50 years and where my father, Cortlyn had died) to Roaring Spring, Pennsylvania (where her youngest daughter Barbi would be her care-giver for the next several years.) In any case my mother's reply was that she thought that maybe she could have a museum of some sort. Well, her collection in itself was probably not complete enough to make a museum, but it was a start.

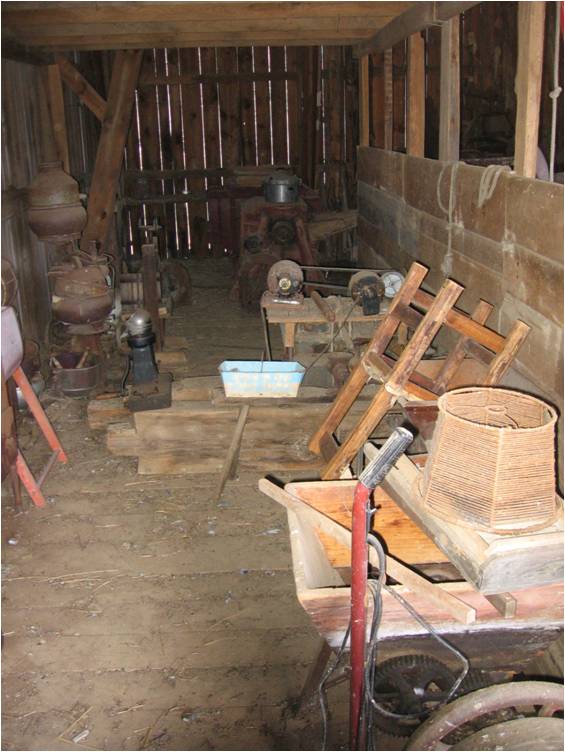

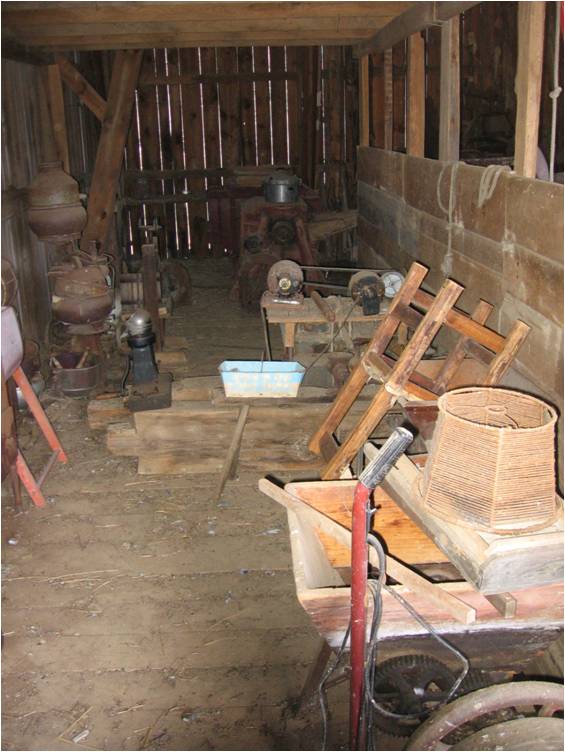

After my mother died and we her children were dealing with the dispersion of an enormous amount of stuff that she had collected, I asked my siblings if I might keep at the farm the primitive, farm-related items. There was not really that much monetary value involved in the items, but I hated to see the collection broken up since it was such a good start and had meant so much to her. I had lived on her farm for about thirty years and had quite a collection of my own. My items were craftsman related. Early I had decided that Babbitt bearing, flat-belt driven, cast iron machinery tended to be easily preservable and restorable and could wait until I reached retirement age. I also had had an interest ever since I had worked in a crafts program in the Peace Corps in Brazil in the interrelatedness of the older crafts and had slowly, whenever possible, accumulated tools that served those crafts – hoping that some day the craftsmen themselves might reappear. My mother’s collection and my own form the basis of the artifacts at the Old Ways Museum.

But, the Old Ways Museum is not intended as a collection of items, but rather as a witness to a direction. That direction is away from modern technology and toward older ways of doing things. A visitor to the museum who is looking for an authentic representation of any particular historical period will be disappointed. I would suggest that such a visitor go to Old Bedford Village or The Keystone Foundry in Hopewell or even the Altoona Railroader’s Museum. But if a visitor is interested in seeing deliberate movement toward ways of doing things in the past, he may have come to the right spot.

This prospectus is an attempt to record those parts of the museum which are actually in place but also in many cases to record my vision of what could be in place -- either within a year after I retire from teaching (about five years) or sooner if a second individual or others would take an interest and help in the effort.

The prospectus will take the form of a very rough draft for a visitor's guide.

VISITOR’S GUIDE TO THE PARTIALLY ACTUAL AND PARTIALLY IMAGINED

OLD WAYS MUSEUM

PART ONE

[Note: Most of what is described is actual with the exception of the 15 waterwheels, only two of which are in place and those two still under construction. The sites for all 15, however, have been developed. Also the buildings to house the sawmill and the planning mill are under construction. ]

The way to approach the Old Ways Museum [henceforth OWM] which would be most in keeping with the intent of the museum would be on foot, or in descending order of preference by horseback, carriage, bicycle, bus, car, or – least desirable because of invasion of noise to the space – motorcycle. Regardless of the mode of transportation, the traveler having come out of Bedford and through Dutch Corner will have first noticed as he rounded the curve at the top of Jew Hill (locally called that in yesteryears because of the "dynasty" of the Oppenheimers – more about which later) the view of the n

The way to approach the Old Ways Museum [henceforth OWM] which would be most in keeping with the intent of the museum would be on foot, or in descending order of preference by horseback, carriage, bicycle, bus, car, or – least desirable because of invasion of noise to the space – motorcycle. Regardless of the mode of transportation, the traveler having come out of Bedford and through Dutch Corner will have first noticed as he rounded the curve at the top of Jew Hill (locally called that in yesteryears because of the "dynasty" of the Oppenheimers – more about which later) the view of the n arrow valley below between said hill and Brumbaugh Mountain to the North. This view is gradually becoming obscured – especially in the summer – by the growth of trees on the side of the hill. That obscurity is welcomed because it gradually builds on to the division between the modern world and the "campus" of the OWM and contributes to a sort of Brigadoon or Shangri-la effect to the hollow. Second after the view a traveler will have noticed the Crown, an unfinished replica of the Elizabethan Rose Theater at the summit of the hill behind the Cherry Tree House. This Cherry Tree House will have been noticed nearly as quickly. It is a very large Pennsylvania farm house and Barbara Camp Antonson’s ancestral home – built by her great grandfather in 1863 outside of Cherry Tree, Pennsylvania, but disassembled at Barbara and Cortlyn’s expense by their son Frank Antonson, moved the 70 miles, and reassembled at the present site starting in 1983 (and continuing). The Cherry Tree House is not part of the OWM, but has a story of its own.

arrow valley below between said hill and Brumbaugh Mountain to the North. This view is gradually becoming obscured – especially in the summer – by the growth of trees on the side of the hill. That obscurity is welcomed because it gradually builds on to the division between the modern world and the "campus" of the OWM and contributes to a sort of Brigadoon or Shangri-la effect to the hollow. Second after the view a traveler will have noticed the Crown, an unfinished replica of the Elizabethan Rose Theater at the summit of the hill behind the Cherry Tree House. This Cherry Tree House will have been noticed nearly as quickly. It is a very large Pennsylvania farm house and Barbara Camp Antonson’s ancestral home – built by her great grandfather in 1863 outside of Cherry Tree, Pennsylvania, but disassembled at Barbara and Cortlyn’s expense by their son Frank Antonson, moved the 70 miles, and reassembled at the present site starting in 1983 (and continuing). The Cherry Tree House is not part of the OWM, but has a story of its own.

Also not part of the OWM but located central to it is Frank Antonson’s home sometimes called locally "The Swiss House". It also has a story of its own.

Having descended the hill the traveler turns right into the OWM. If he is observant he will notice that this entrance is a single lane, unpaved, and with a grassy strip in the middle. Even before the gate the traveler has passed old ways of doing things in that there is a basket willow hedge separating the OWM from the road and a filtering ponds on the visitor’s right. At the gate the visitor should notice that water is flowing under a pair of tire-width low arches. This water is flowing to the visitor’s left in a leat or headrace toward the lowest of the various waterwheels on the north side of the road – the waterwheel at Nina Falls.

Having descended the hill the traveler turns right into the OWM. If he is observant he will notice that this entrance is a single lane, unpaved, and with a grassy strip in the middle. Even before the gate the traveler has passed old ways of doing things in that there is a basket willow hedge separating the OWM from the road and a filtering ponds on the visitor’s right. At the gate the visitor should notice that water is flowing under a pair of tire-width low arches. This water is flowing to the visitor’s left in a leat or headrace toward the lowest of the various waterwheels on the north side of the road – the waterwheel at Nina Falls.

The gate is normally open and is midway in a short allee of sycamores. To the right and to the left of the visitor are to be found parking lots – but these also serve as cow pastures (and the visitor should be aware of where he places his feet). Forming an up-slope boundary to these two parking lots is another leat or headrace once again crossing u nder a pair of tire-width low arches. This water, however, is flowing to the visitor’s right. It is on its way to join water coming from Cort Dam in Oppenheimer run and from the tailrace of the overshot waterwheel at Jane Falls to then pass under an undershot water wheel at Elizabeth Falls beside a small springhouse-dairy-brewery before becoming the selfsame water that the visitor first noticed passing to his left under the lane.

nder a pair of tire-width low arches. This water, however, is flowing to the visitor’s right. It is on its way to join water coming from Cort Dam in Oppenheimer run and from the tailrace of the overshot waterwheel at Jane Falls to then pass under an undershot water wheel at Elizabeth Falls beside a small springhouse-dairy-brewery before becoming the selfsame water that the visitor first noticed passing to his left under the lane.

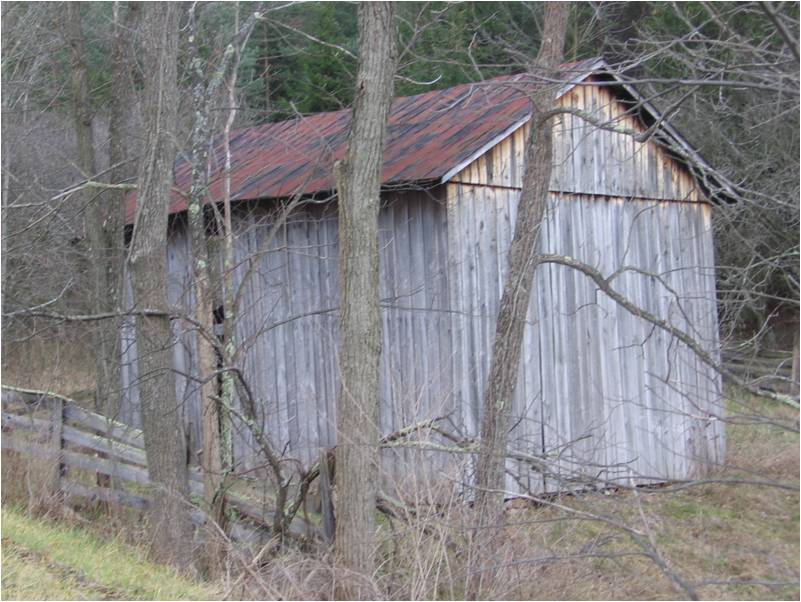

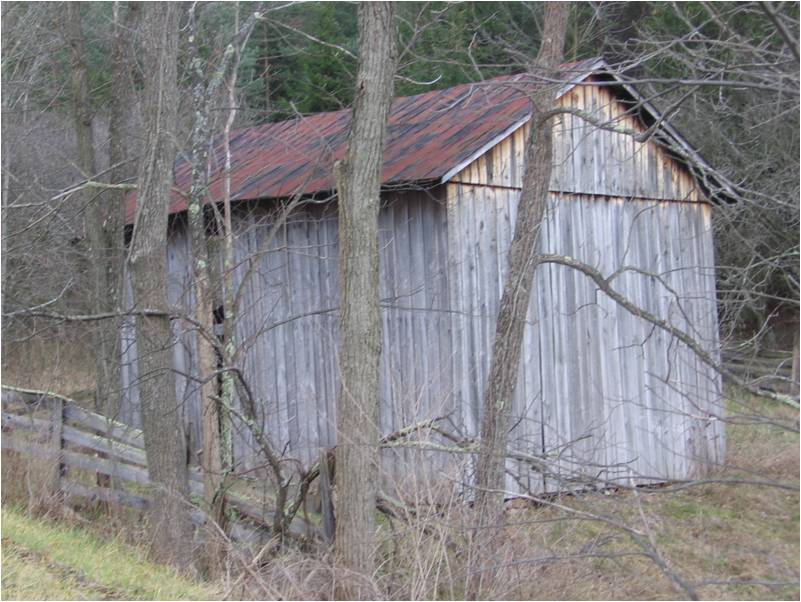

If the visitor will stand and look around from the lane between the cow pasture parking lots he will see nine buildings. There are four more buildings that he cannot see from this vantage point. Those four are the Cherry Tree House, the Crown, Frank Antonson’s home – sometimes locally called the Swiss House – and an outhouse that went out of use in the 1950's. Of the buildings that the visitor sees the most imposing are two nearly matched gambrel-roofed plank barns. Both were built around 1960. The up-slope one to the left of the lane is the older and serves as a cattle barn. The newer on the right of the lane contains the main collection of artifacts of the OWM and will be discussed in detail when the visitor enters it.

Closest to the standing visitor and beneath a huge ash tree (in lieu of a "spreading chestnut") to the right of the lane is a small blacksmith’s shop. This is built on a small old foundation of a building the original use of which has so far not been established.

ARCHAEOLOGY AND FAMILY HISTORY.

A photograph of the then Schnably property taken about 1875 of this same property – now referred to as the campus of the OWM – shows ten buildings. The Schnablys were the second "dynasty" to own the property. The first was the Bowsers, the third was Oppenheimers, and the fourth since about 1942 and to the present is the Camps. All of the buildings in the photograph are gone. James J. Camp, Barbara's father, purchased the property as a result of a sheriff’s sale. The story is that he bought it at his son’s request so that this his only son, Frank Bradley Camp, could come back to it after World War II. Being a pilot of a spitfire in the North Africa campaign, Frank was killed in action and never returned. The entire initial 600 acres eventually went to Barbara and her sister Helen Camp Palmer, who divided it. Nina Palmer Sweeney, Helen's oldest of three daughters now owns that 300-acre parcel adjoining the OWM to the East. That parcel has a story of its own and it is Frank Antonson’s and Sweeney’s intent to someday reconstruct that history.

The buildings on the "Camp Ranch" as the property came to be called after J.J. Camp purchased it were all in such disrepair by 1942 that, with the exception of a log cabin on Nina Palmer's property which he reconditioned and added on to, all were dismantled. Parts of some of those buildings original to the Schnablys are still to be found in various of the buildings that Camp went on to construct, but none of this new generation of buildings occupies the exact same foundation of an earlier one.

At some point Camp had a major bulldozing done. It is my assumption that at this time he smoothed over the sites of many of the earlier buildings. In addition to the ten buildings visible in the 1875 photograph there is archaeological evidence of many more. In fact one local "historian" has told me that at one point the population of this narrow valley was about 100 people. The most that have ever lived there permanently since at least 1940 until 2006 is seven for two winters and four for the rest of the time. What supported those 100 people, if in fact that figure is true, were the iron mines developed by the Oppenheimers. It was during their "dynasty" and from about 1885 until about 1920 – or when the iron fields of the West were developed -- that the soil of the land which at best had been mountain ground was essentially destroyed for farming by the strip mining and subsequent bulldozing by Camp to smooth out what he could. At some time in the late 1950's Camp also bulldozed out a pond from a spot (it is now believed) earlier occupied by at least two buildings and a spring. This bulldozing has been like the complete disassembly of a jigsaw puzzle before one starts to reassemble it. Much has been hidden, but in a sense thereby preserved

Perhaps at this time it should also be mentioned that as part of the iron ore removal process a narrow gauge railroad was built up through the valley from near Cessna. In some places the earthworks remaining from this railroad are apparent, but they are not obvious. It remains for the future to map out the exact route of it and its branches together with the mine cart track that brought ore down from an inclined plane below a shaft mine up on the mountain. In many places in the forested part of the OWM the evidence of the iron mining is very apparent.

BACK TO OUR VISITORY STANDING IN THE LANE AND LOOKING AT THE SMALL BLACKSMITH’S SHOP. (This shop is imagined.)  Slightly behind that shop is another small building housing a flat-belt driven four siding planer. This is a machine dating from about 1890 and given to the OWM by Joseph Elyard. To the left of the lane and up a short grade is a larger building housing a flat-belt driven sawmill. This mill dates from about the 1890's and was initially driven by a steam engine. It was manufactured by the Farquahar Company and had an unusual friction disc drive for the carriage. The track of the sawmill is 50 long. Its history is that Frank Antonson bought it from Ralph Kegg in 1974, who had bought it from Harve Imler, presumably the first owner who operated in a little downstream from Imlertown. As of 2006 at least two people that attend Messiah Lutheran Church can remember the mill being run by steam. Both of the machines, the planer and the sawmill, of course have Babbitt bearings. The sawmill includes a swing saw and a sawdust drag. The machines will have to be run by a tractor’s power take off or some other gasoline e

Slightly behind that shop is another small building housing a flat-belt driven four siding planer. This is a machine dating from about 1890 and given to the OWM by Joseph Elyard. To the left of the lane and up a short grade is a larger building housing a flat-belt driven sawmill. This mill dates from about the 1890's and was initially driven by a steam engine. It was manufactured by the Farquahar Company and had an unusual friction disc drive for the carriage. The track of the sawmill is 50 long. Its history is that Frank Antonson bought it from Ralph Kegg in 1974, who had bought it from Harve Imler, presumably the first owner who operated in a little downstream from Imlertown. As of 2006 at least two people that attend Messiah Lutheran Church can remember the mill being run by steam. Both of the machines, the planer and the sawmill, of course have Babbitt bearings. The sawmill includes a swing saw and a sawdust drag. The machines will have to be run by a tractor’s power take off or some other gasoline e ngine until such a time as something older could be used. It is Antonson’s intent to eventually power them either by wood gas (a technology of the early 20th century) or methane engines. The rest of the machinery in the OWM is meant to be powered by waterpower. (The buildings for these two mills are under construction).

ngine until such a time as something older could be used. It is Antonson’s intent to eventually power them either by wood gas (a technology of the early 20th century) or methane engines. The rest of the machinery in the OWM is meant to be powered by waterpower. (The buildings for these two mills are under construction).

A WORD ABOUT THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDINGS BROUGHT TO THE OWM BY ANTONSON. It has only been with considerable deliberation that Antonson has decided to put the board siding on the inside rather than the outside of any timber framed buildings that he reconstructs. In Pennsylvania this is usually not done and is not original to the buildings. Barns and sheds typically have vertical board siding on the outside of the framing. Although framing is often displayed to give a Tudor or half-timbered look to houses, Antonson was not willing to do something just for looks. However, after considering even older building techniques in Switzerland and Germany – sources for Pennsylvania’s culture of barns – he found that boarding on the inside was commonly done – with "nogging" or "infill" added on the outside and then plastered when desired. This decision gives several of the buildings at the OWM a medieval and European look – including, of course, the Crown, earlier mentioned.

AGAIN BACK TO THE VISITOR STANDING. The remaining two buildings that the visitor can see, both with the sawmill and two barns helping to surround a level "plaza",  are the "wagon shed" now a small animal barn and a "wellhead-rootcellar-oneroomschoolhouse-dovecote." This latter building’s original intent was to cover a dug well that had been filled in but continued to issue water in the wet season. Antonson re-dug that well and repaired its sandstone rubble lining. At that time he also drained it at a certain level so that water would not come out of the top and added a root cellar to it. More about this building later, but for now it might be said that the top of that original dug well is barely visible in the Schnably photograph.

are the "wagon shed" now a small animal barn and a "wellhead-rootcellar-oneroomschoolhouse-dovecote." This latter building’s original intent was to cover a dug well that had been filled in but continued to issue water in the wet season. Antonson re-dug that well and repaired its sandstone rubble lining. At that time he also drained it at a certain level so that water would not come out of the top and added a root cellar to it. More about this building later, but for now it might be said that the top of that original dug well is barely visible in the Schnably photograph.

This standing visitor in addition to the buildings just described can see from that one spot seven of the OWM’s 15 waterwheels. (Thirteen of these waterwheels are imagined, but the sites for all but one are prepared.) These waterwheels will be described as they are encountered in a walk through the OWM.

A WORD ABOUT THE SURFACE WATER IN THE OWM. The various waterwheels which will be described in detail elsewhere are made possible by some 25 years of mostly hand digging on Antonson’s part. Given that the soil was poor for farming and even grazing, and given that Barbara Camp Antonson had insisted that no fertilizers, lime, sprays, or plowing were to be used on the property. Antonson turned to irrigation. The system he developed is extensive and the subject of his book The Meadow Book written in the 1980's but privately published among family members with only 10 copies made. Stated simply he in many places diverted water from the natural courses by very low dams and then led that water on perfect contour lines when possible or slightly sloping lines in the forested areas so that the water could be used to irrigate pasture. (These perfect contour lines serve to very precisely reveal earthworks of the past and since they are essentially neutral in terms of design they function a little like a crayon in a brass rubbing) These low diversion dams contain no exotic materials but are just made of what is there at the stream. Accordingly they always leak to some extent and do no stop the flow of water in the natural run. Also, since they are so low and on a contour, during flooding they are immediately overtopped and the system is not damaged except that sometimes silt if trapped near them. This system, he eventually found out, was a cross between what the English called "water meadows" and the Swiss called "bisses", "wasserleitungen", or "suonen". He had first seen the technique used in Senegal and in Peru. The same system leant itself to the development of small waterwheel sites where the water was allowed to drop. The drop structures bear the names of various women – mostly family members; and the dams of various men – again, mostly family members. Hence, Jane Falls, Adam Dam etc. The system locally anticipated the use of wetlands for water purification and for conservation, which became widely accepted some ten years after Antonson had begun his waterworks in 1981. In Western United States such use of water would not be allowed because the water itself is often owned by someone other than the landowner – this from the Arabian and Spanish heritage. In the Eastern United States, however, "riparian rights" apply – this from England and Northern Europe. By riparian rights a landowner may use the water that flows through his property, but he must return it to the natural run.

LET’S GET THAT STANDING VISITOR MOVING. As the visitor walks up the lane he goes up a gentle grade, passing on his left a small water whee l that uses for its fall the apparent remains of an old barn foundation – this location, however, is only revealing itself slowly. This falls is called Sister Jane Falls. Just behind it is Lyn Falls. Then the sawmill earlier mentioned is passed on the left and the planning mill on the right. Arriving at the level "plaza" if the visitor turns to his right he can go in the lower "horse" barn that houses most of the collection of artifacts. In this plaza there is evidence of prior buildings that were not laid out on the same axis that the Schnably buildings and Camp’s buildings are. This is also true of the springhouse below in the meadow at Elizabeth Falls. Their layout probably indicates a date earlier than the Schnablys. Going in the barn door, the visitor might be struck by the beauty of the gambrel-roofed plank barn construction. It allows for a barn floor completely free of posts, since the structure is held up by six pairs of opposed high-arching trusses that rest on the foundation walls.

l that uses for its fall the apparent remains of an old barn foundation – this location, however, is only revealing itself slowly. This falls is called Sister Jane Falls. Just behind it is Lyn Falls. Then the sawmill earlier mentioned is passed on the left and the planning mill on the right. Arriving at the level "plaza" if the visitor turns to his right he can go in the lower "horse" barn that houses most of the collection of artifacts. In this plaza there is evidence of prior buildings that were not laid out on the same axis that the Schnably buildings and Camp’s buildings are. This is also true of the springhouse below in the meadow at Elizabeth Falls. Their layout probably indicates a date earlier than the Schnablys. Going in the barn door, the visitor might be struck by the beauty of the gambrel-roofed plank barn construction. It allows for a barn floor completely free of posts, since the structure is held up by six pairs of opposed high-arching trusses that rest on the foundation walls.

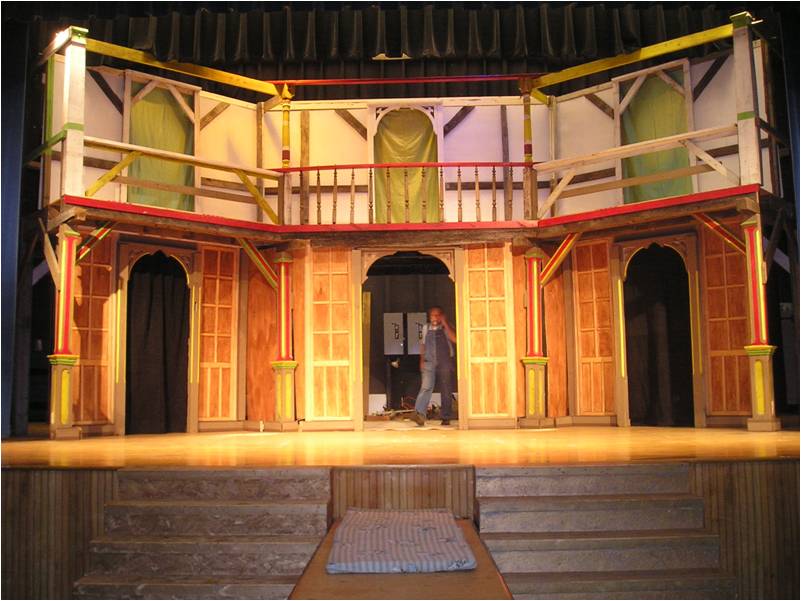

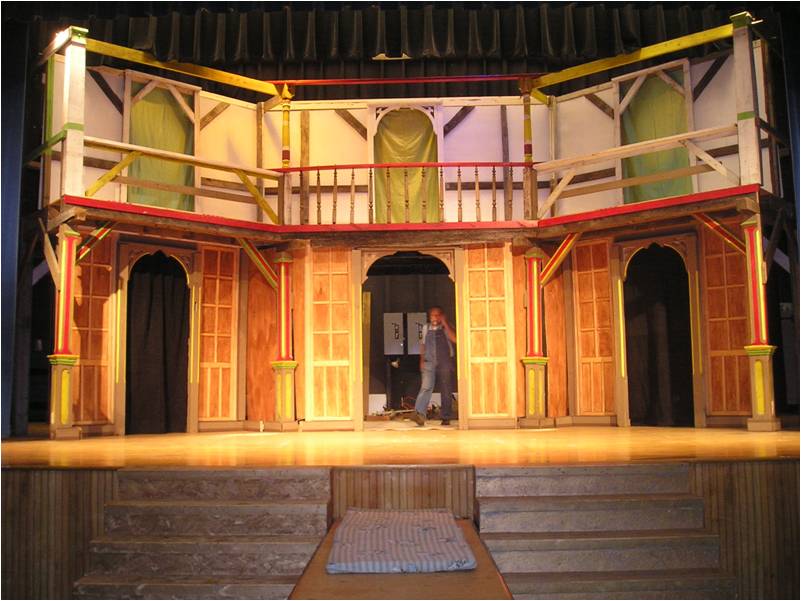

Inside the "horse barn" the most striking thing will be the Jewel, a transportable set which can serve as the two-storey stage of an Elizabethan theater. In fact the Jewel belongs to The Shakespearean Troupe, a Bedford High School club that between 1997 and 2006 produced 24 Shakespearean plays. When weather and other circumstances permit, the Jewel can be moved to the Crown, the replica of the Rose Theater mentioned earlier. Performances of Shakespearean plays can take place within this barn, but the lighting is natural from the windows and a cupola centered above the audience. (This cupola is imagined, and for the present an attempt at the same effect is made by a double bank of fluorescent lights hung close to the rafters.) Another kind of light is offered whimsically in this barn. It was used for a wedding reception for Barbi and Jeff Hetrick (Barbi is Barbara Camp Antonson’s youngest child). At that time Antonson converted 12 milker heads into "chandeliers" by putting light bulbs in the teat cups. These he hung from the trusses. They remain there.

Until the summer of 2007 this horse barn had no windows and in the regular darkness inside bats and pigeons flourished. During that summer, however, a dovecote was built for the pigeons and better-placed bat houses for the bats. Many windows were also cut into the barn to naturally illuminate the various craftsmen’s benches around the periphery of the barn. These workbenches, starting by looking with the visitor’s back to the barn door and then turning a full circle to the right are the following: a leather/harness/cobbler’s shop, a wheelwright/wainwright’s shop, a window/doormaker’s shop, a cooper’s shop, and a seamstress’ shop.

In addition to these shops the barn floor has the following antique machinery all driven by line shafting from below and to there from the adjacent waterwheel at Jane Falls: barn machinery including a burr mill, a cob breaker, a seed cleaner, a corn sheller, an apple cider press; and woodworking machinery including a cut off saw from an old pin mill factory, a shaper, and a combination ripping saw and jointer. All of that machinery is flat-belt driven. There is also a display of various hand tools for fieldwork.

Finally at the back of the barn floor if the visitor is facing the Jewel and on a platform one storey higher is a dual manual reed church organ out that Pastor Raymond Short donated to the OWM. This reed organ is supplied with suction by the "bellows" at the waterwheel at Jane Falls.

The restrooms for the OWM are essentially two-storey outhouses, which are reached from the inside of the "horse barn" on the side away from the door. (Barbara Camp Antonson used to say that a two-storey outhouse was built into the Schnably house by the time that Camp had bought it.) The waste is delivered straight into a biodigester to which is also added the horse manure and sawdust from the stables below. This biodigester produces gas to power the planning mill earlier mentioned.

The restrooms for the OWM are essentially two-storey outhouses, which are reached from the inside of the "horse barn" on the side away from the door. (Barbara Camp Antonson used to say that a two-storey outhouse was built into the Schnably house by the time that Camp had bought it.) The waste is delivered straight into a biodigester to which is also added the horse manure and sawdust from the stables below. This biodigester produces gas to power the planning mill earlier mentioned.

Leaving the "horse barn" by the same door that he entered, the visitor should take a turn to his right and go down a slope toward "the mill over Jane Falls. Half way down this slope there is a "landing" or sorts. This has recently been discovered to be the foundation of the tower that was added by the Oppenheimers to the Schnably house in the picture of 1875. To the visitor’s left, as he stands on this landing, is the foundation of the old pictured house. Around the year 1956, after he had torn the house down and used what lumber and building stone that he could, Camp had the remaining walls above grade pushed in and began to fill the foundation in with shale from the "ore dumps". This Antonson, aged about 13 then, helped a little to do and occurred when Camp still had mules and a hired hand who lived in what was then the foundation of the "Swiss House". Now Antonson is gradually re-excavating the foundation and exposing the original walls. Centered in this foundation is "The Beast", a large incinerator with an afterburner which served as the initial retort for charcoal making. If the visitor now goes on down to the level of the foundation floor and looks into that foundation, to the left of The Beast he will see a work bench, forge, crucible furnace, and cupola furnace for working with hot metal and fire – even potentially casting iron. To the right of The Beast he will see a matching workbench used for the processing of the results of combustion in The Beast – namely the ashes and metals that result from incineration. By the time this material has been sorted it can be recycled or used on site as fertilizer. At the back of this side of the foundation is a very large "fireplace" able t o contain one to three 275-gallon oval tanks. These are used for the making of charcoal in quantity. Also in this foundation along the eastern wall is the waterwheel at Jess Falls. This low volume waterwheel powers a light blast of air to the forge or the fan for drawing off fly ash from the screening process. Ultimately the floor of this foundation should never freeze even though it is, when not tented, open to the sky because along the floor runs water – not only

o contain one to three 275-gallon oval tanks. These are used for the making of charcoal in quantity. Also in this foundation along the eastern wall is the waterwheel at Jess Falls. This low volume waterwheel powers a light blast of air to the forge or the fan for drawing off fly ash from the screening process. Ultimately the floor of this foundation should never freeze even though it is, when not tented, open to the sky because along the floor runs water – not only from Jess Falls, but more importantly, from the pond on its way to Jane Falls. This latter headrace comes out of the pond as if it were from a spring house and does not freeze in winter.

from Jess Falls, but more importantly, from the pond on its way to Jane Falls. This latter headrace comes out of the pond as if it were from a spring house and does not freeze in winter.

Just past the old house foundation is a wood yard for storing scrap wood intended for charcoal making and past that several of the various "terraces" related to the surface water technique earlier described converge as the slope gets steep into a an earthen stairway with water passing crossways at each step. This is called "The Wide Stair".

With the foundation and The Beast at his back the visitor may look across the headrace to Jane Falls at Barbi’s laundry and bathhouse. Here water may be made to bypass Jane Falls and flow in a variety of fountains and tubs, including a large "hot tub" made from a section of an eight-foot diameter wooden silo. Water for this complex may be heated by a wood-burning boiler.

Turning to his right and walking along the flow of water a few feet, the visitor comes to the mill over Jane Falls. This is a building that Camp had built across the road to house his young cattle. But as the pasture connected to it grew up into evergreens and since it was put on very inadequate foundation and sills, Antonson disassembled it in the summer of 2007 and put it over the waterwheel and "bellows" at Jane Falls. Said eight-foot overshot waterwheel by rope drive powers the line shaft within the horse barn or the water may be directed through a pentstock between the mill and the horsebarn down to a Pelton wheel, which can be used to generate low voltage direct current.  The main artifact of this mill at Jane Falls is on the wooden floor above the wheel. There is centered a flat-belt driven predecessor to what one might now call a "Shop Master". It appears to be one-of-a-kind, and is built up out of channel steel welded together. Meant to be driven by a flat belt from a tractor, the pulleys and cone pulleys underneath its deck drive five cutting heads – a band saw, a morticer (or drill press), a ripping saw, a cut off saw, and a jointer. It is on wooden skids and was once meant to be pulled around to its place of work. Also included in the Mill at Jane Falls is a collection of flat-belt pulleys, large v-belt pulleys, shafts, couplings, bearing hangers and other components to a line shaft system.

The main artifact of this mill at Jane Falls is on the wooden floor above the wheel. There is centered a flat-belt driven predecessor to what one might now call a "Shop Master". It appears to be one-of-a-kind, and is built up out of channel steel welded together. Meant to be driven by a flat belt from a tractor, the pulleys and cone pulleys underneath its deck drive five cutting heads – a band saw, a morticer (or drill press), a ripping saw, a cut off saw, and a jointer. It is on wooden skids and was once meant to be pulled around to its place of work. Also included in the Mill at Jane Falls is a collection of flat-belt pulleys, large v-belt pulleys, shafts, couplings, bearing hangers and other components to a line shaft system.

Finally, continuing in the direction the visitor is facing, he can walk through the lower level of the horse barn. Along that 80 foot on his right he will pass in sequence a shop for cold metal working, a waterwheel-building shop a carpenter's shop, and a mechanic's shop. On his right he will be passing a large antique flat-belt driven metal lathe, a mortising machine from the shops of the now-torn-down paper mill at Williamsburg, a series of grindstones, and then stables.

Coming out of the lower level of the horse barn the visitor will be facing west and, passing the planning mill and the blacksmith’s shop on this left, he will return to the lane that he started up from the parking lot.

A wider walk and a longer stay at the OWM would take the visitor around the pond and through the meadow up to the Crown, to four other waterwheel sites, on a tour of Antonson's waterworks, and perhaps more, but that should be enough for a first visit.

PART TWO

HOWEVER, in case the visitor is ready for a little more, here is another short route. Walking east with the planer and main building on his left, the visitor will pass low-terraced gardens to his right and then will come to a point that the tail waters from Jane Falls join the tail waters from three of the falls to the west of the lane and a new leat brought from Oppenheimer run at Cort Dam. There is a crossing here and immediately on the left the visitor will see (or hear) the Pelton wheel. It is an alternative to the overshot wheel at Jane Falls. Both can run at once, but usually only one will be running.

A NOTE ABOUT THE USE OF THE ENERGY FROM THE VARIOUS WATER WHEELS. As a default to another use of the energy, the various waterwheels can turn small generators. The low voltage current made by these is not transported but rather used in on-site electrolytic cleaning of old tools or pieces of hardware and the hydrogen and oxygen resulting from the electrolysis of water is independently stored.

From the lower side of the mill at Jane Falls the visitor will see a tilt hammer and a very large forge – both powered by the overshot wheel. The bellows for the forge is a large flat-belt driven, Babbit-bearing, two-cylinder compressor originally intended to be driven by a large-horsepower engine of some kind. At the OWM it runs slowly and only delivers a blast appropriate for the forges or the blast furnace.

The tilt hammer (these are sometimes called trip hammers) has a hammer head that weighs about 75 pounds which falls on an anvil made up of o various elements – one of which is the weight from the back of a bulldozer. The principal purpose of this tilt hammer is to make wrought iron.

Passing Barbi's laundry and bathhouse on the left the visitor moving toward the pond will come to the tannery. As the visitor approaches the tannery he will be walking through a terraced meadow – each terrace of which in addition to serving as pasture serves as a filtering bed for any waste that comes from the activities upstream of it.

Walking along the north side of the pond the visitor will see to his left the front of the Cherry Tree House with its juniper-covered bank below it and a long greenhouse just below that. This green house covers part of the water supply approaching Jess Falls. The rest of the supply for Jess Falls comes from the combined tail waters of Barbi Falls and Waterwheel – the highest of the OWM – and the water diverted by Adam Dam where a lane crosses the natural run. Between the long narrow "greenhouse" and the pond is a lane – almost on a contour line – and a terraced pasture which is gradually being converted into a parterre. Around the curve of the hill to the East of the Cherry Tree House is an area of terraced gardens and pasture below the leat bringing water from Jeff Dam to Barbi Falls. Rounding the upstream, eastern end of the pond involves crossing a wooden bridge then passing another of the waterwheels of the OWM. As the visitor crosses that bridge he can see to his left in a small wetlands and example of a dawn redwood. This is one of two in the OWM. What is so special about this tree is that it was thought to have been extinct and was only known through fossil evidence until one was found in China. Since then it has been introduced around the world. It is a fast-growing deciduous conifer. (This dawn redwood is just one example of Barbara Antonson's love of landscape architecture,which she tried to express on the Camp Ranch. There are many trees that have been planted in memory of someone – and a few other unusual specimens. But that subject should be considered elsewhere.) There are actually two waterwheel at the eastern end of the pond. This site is called William and Helen Falls. William Falls serves as a bypass from the pond when water needs to be diverted. Helen Falls, the other side of it allows the water to fall into the pond -- water delivered from Sven Dam (on Oppenheimer Run) and Frank Dam (on the unnamed creek that most closely feeds the pond)

Walking along the north side of the pond the visitor will see to his left the front of the Cherry Tree House with its juniper-covered bank below it and a long greenhouse just below that. This green house covers part of the water supply approaching Jess Falls. The rest of the supply for Jess Falls comes from the combined tail waters of Barbi Falls and Waterwheel – the highest of the OWM – and the water diverted by Adam Dam where a lane crosses the natural run. Between the long narrow "greenhouse" and the pond is a lane – almost on a contour line – and a terraced pasture which is gradually being converted into a parterre. Around the curve of the hill to the East of the Cherry Tree House is an area of terraced gardens and pasture below the leat bringing water from Jeff Dam to Barbi Falls. Rounding the upstream, eastern end of the pond involves crossing a wooden bridge then passing another of the waterwheels of the OWM. As the visitor crosses that bridge he can see to his left in a small wetlands and example of a dawn redwood. This is one of two in the OWM. What is so special about this tree is that it was thought to have been extinct and was only known through fossil evidence until one was found in China. Since then it has been introduced around the world. It is a fast-growing deciduous conifer. (This dawn redwood is just one example of Barbara Antonson's love of landscape architecture,which she tried to express on the Camp Ranch. There are many trees that have been planted in memory of someone – and a few other unusual specimens. But that subject should be considered elsewhere.) There are actually two waterwheel at the eastern end of the pond. This site is called William and Helen Falls. William Falls serves as a bypass from the pond when water needs to be diverted. Helen Falls, the other side of it allows the water to fall into the pond -- water delivered from Sven Dam (on Oppenheimer Run) and Frank Dam (on the unnamed creek that most closely feeds the pond)

Coming around the pond to its south the visitor will see Cort Dam below on his left. This is the second place in Oppenheimer run that water is diverted by a low dam into the OWM. The water from Cort dam joins the tail waters as described before, but first passes through the meadow, forming a last filtering bed above the springhouse.

The springhouse has been reconstructed on its original site. However, the only clear evidence of the original building is the walled up spring itself and a large stone across where the water leaves the spring. This springhouse has been made into a combination brewery and dairy. The waterwheel beside it at Elizabeth Falls is an undershot wheel using a flow of water that now is the maximum that the combined streams can supply. Passing this springhouse, the visitor can cross a small covered bridge placed in line with an original "causeway", whose exact purpose has still not been established, and thereby return to the parking lot.

That should be enough for a one-day's visit to the OWM.

PART THREE

HOWEVER, for those who would like to cover a little more distance and don’t mind a little hiking, here is a third route for the visitor to consider.

Leaving the western parking lot/pasture and heading up hill, the visitor will be crossing terraces of a watermeadow for a few yards. (At this point behind the visitor and across the "parking lot" eventually there will be a small arboretum of waterloving evergreens to the east of the natural water course and dry-ground-loving evergreens to the west of said watercourse and approached by climbing the old "cow stair". The arboretum is located there partially to hide the sole pole light visible at the OWM.) Sister Jane Falls will be on the right – just below the sawmill – receiving its water from the tailwater of Lyn Falls – also just below the sawmill. Lyn Falls is over the drain from the cow barn. Antonson had this drain put in by a backhoe in a long-continuing effort to keep the cow barn from being wet. There had been in effect a spring inside the cow barn, making it very difficult to keep clean. Antonson had the backhoe go into the barn itself as far as it could and then continue on the uphill side of the barn to the dug well mentioned earlier as being covered by a one-room-school-like wellhouse. Eventually Antonson was able to dry out that barn but it took years and an addition to the roof line on the uphill side. He suspects that in fact there was a spring or well inside the barn that Camp filled in and covered but which continued to bleed water. Apparently the original drain to that spring eventually reopened.

Passing Lyn Falls and turning to the left the visitor, now hiker, should notice that water is issuing from a spring on his left. The is water bleeding from the base of an old strip mine that was bulldozed in. That spring revealed itself as an "olho d'agua" as it is called in Portuguese and Spanish. Translated that means an "eye of water". This was before Antonson opened it. (Perhaps it might be of interest to know that an "olho d'agua" was thought beautiful enough by Dupont that when he built the Longwood Gardens he included a huge artificial one). By following the water supply to Lyn Falls the hiker will pass evidence of a spoil bank for said strip mine and will come to the waterwheel at Grace Falls. This falls has a relatively high drop of water and its wheel is a combination overshot wheel and impulse wheel – using the shock of water shooting down a sluice as well as the weight of that water once it settles in the buckets of the wheel. The supply to Grace Falls comes from the woods some 300 yards to the North along a contoured leat from the low Joyce Falls (named after Joyce Herncane) and the diversion dam Michael Dam (named after her husband). This leat forms the upper limit of an area of irrigated pasture crossed by about five other contoured ditches below it.

From Grace Falls if the visitor follows a lane straight up the hill he will come to The Crown – the unfinished replica of the Elizabethan theater, the Rose. This building sits directly on top of the hill and is surrounded by a "moat", really just a ditch, which in some seasons can be filled. The theater was begun by Antonson from the material resulting from the removal of a shed from the Charles Hershberger barn plus materials from as many as ten other buildings that Antonson demolished. This theater is to be three storeys high but only got to two before Antonson had to stop for lack of sufficient and adequate wood. He decided to wait for the use of his sawmill and to turn his attention to getting it running. It is of some interest that in Lennox, Massachusetts, a similar building was begun at about the same time. That building was backed by an initial grant of one million dollars and had a total proposed budget at first of 42 millions. At present it appears that the Lennox project has still not been accomplished. Antonson has about 400 dollars invested in his attempt. Most of the theater is self-explanatory, but it should be known that under the stage are about six or eight 20-foot American Chestnut logs and that the stage itself is made up of 20-foot American Chestnut 2-inch planks heavily damaged and weakened by weathering in the building that they came from.

Heading toward the mountain and the woods to the north from the Crown the visitor will enter a young forest the history of which is that it was at one point pasture, then a plantation of pines (which Camp had timbered) and then the young growth that it is now. Antonson calls this wood William's Woods, in honor of Shakespeare. In the spring time water passes down through this woods in ditches even though it is on the top of a ridge. That water is part of what is gathered by a system of ditches on the mountainside that continually gather water from the various springs. Antonson was inspired to attempt this water system after he visited his daughter Erica in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. There he had seen what was done with water in the Parque Central. Later, he noticed that in Paris in the Bois de Boulogne water was guided through in a similar way. This water system is only possible to maintain in the springtime.

At the top of William's Woods is a small knoll separated from the mountain proper by a very low saddle. As with the Crown, water is guided completely around this little high spot before it is allowed to drop through the Woods. Antonson had once considered this as the spot for his theater because like the actual site it needs no excavation to establish a round, level building site.

At this point to go further up the mountain would involve a considerable hike and would probably require a guide to find the various points of interest. HOWEVER, SINCE WE’RE HERE, I will describe the hike with the understanding that a visitor without about an extra hour to spend and who does not relish hiking up the side of a mountain will turn around and head back down at this point. For the visitor who wants to continue on I should say that we will return to this spot after we take a loop on the mountain side. A set of brackets will indicate the beginning and the end of this extra hike.

[Heading straight up the mountain along an old logging road in the springtime or when considerable water is running, the hiker will be accompanied by a sometimes roaring flow of water rushing down parts of said road. This might appear to be a very bad conservation or logging practice, but actually the "gulley" that has developed from this water is not like one that can be seen on logging roads that have not had adequate cross channels put into them in that this gulley would not exist at all without considerable maintenance. It is true that the water has carved itself out a route and that it sometimes carries considerable eroded material, but the process has been self-limiting and the eroded material gets deposited on the spine of the ridge as it passes on through Williams’s Woods.

While I am discussing this water supply I should explain that as we hike up the left (west) side of the loop we will see that wherever possible water has been diverted to the right (east), but as we come back down the east side of our loop we will see that water wherever possible has been diverted to the west. The result of this gathering is that water has been made to flow in its most unnatural location – the spine of a ridge instead of the base of the two hollows on either side. In ideal conditions that water is kept "perched" on the ridge all the way to behind the Cherry Tree House and in the process keeps wells full and various springs flowing.

Shortly after starting up this road a very keen observer might be able to notice that the road has been cut through an older mine cart track. That mine cart track runs on a very consistent curve, apparently established by some kind of engineer, between the end of the narrow gauge railroad below the hiker and to the west and the location of an inclined plane above and to the east that during the iron mining period brought the ore down from several shaft mines. The other location of shaft mines on the farm is at the end of the narrow gauge railroad just mentioned. Practically the only evidence left of this mining is the earthworks. A visitor with a metal detector once found a railroad spike along the mine cart track, and Antonson once found a bearing block at the top of the inclined plane, but all other metal was gathered up and apparently scrapped. A hike along this mine cart track to the sites at either end would involve another hour and will not be further mentioned here except to say that as part of the lower eastern complex there is a tight collection of three tiny foundations – two oval and one square with evidence of a fireplace – that were referred to as the "Nigger Huts" by Ronald Hengst, whose father Ralph Hengst logged with mules for Camp, lived beside Camp’s property, and knew it very well.

Speaking of Ronald Hengst, it was from him that Antonson found out about the "log drag" which comes straight down the mountainside slightly to the east of the road the hiker is ascending. This log drag is too narrow for any form of pulling except by horses or mules and ends just about at the same point that the most recent logging road that the hiker is on cuts through the mine cart track.

Climbing a little further along this road the hiker passes along Lotte Falls and then comes to Giselle Falls, which brings water right over an old bulldozed bank used for loading logs onto a truck. Giselle was Erica Antonson's closest friend when she was living for a year in Brazil and she is the only one who was never to the farm and yet has a falls named for her.

Above Giselle Falls there is a confluence. Here the hiker should begin a loop by going up the western, or left hand side. He should will water for this whole loop. Connie Falls brings water down from where the most major vehicular route up the mountain crosses the slope on a contour. At the western end of the part of this road on an approximate contour is Tennessee Spring. Above that is Joy Falls, passing through a cut made anciently as water crossed the edge of the first "bench" of the mountain. Above that there is a whole series of "prises d'eau" or tiny diversion dams that send water eastward. Eventually he will arrive at two springs, one above the other. These will rarely go dry in a droughty year and represent the highest surface water on this part of the mountain.

By heading eastward across the mountain the hiker will begin to encounter water that is being diverted to the west at many other "prises d'eau". The highest of these starts at a spring at the base of a triple-trunked cucumber tree. That water can be brought as far as past a turkey feeder that hunters many years ago made out of a wire spool and brought there. Reaching that spring will be the highest point of the loop and from there the hiker should start down.

On the way down in places too numerous to mention he will see water diverted to our right. Eventually he will come to water evidently coming from another source further to the east, his left. This he will encounter just past "Adam's Chair". (It should be noted that the hunters who enjoy this land have an entirely different set of names for the various places the visitor is passing.) Adam's Chair is just above Katia Falls. By following a logging road that arrives at his left at the same spot as this water, the hiker can go along Kirsi Falls and pool, Sandra Falls and pool, Vanessa Falls and pool, Erica Falls, and then finally arrive at that water's source, The Hermit Spring. Rarely in a droughty year this spring will go dry, but normally in the spring it is possible to return to the parking lot of the OWM walking in the water of manmade watercourses for the entire trip from the Hermit Spring all the way to Nina Falls.

The hiker could from here head directly down the mountain and come to the upper shaft-mining and inclined-plane remains, but it is much more fun to follow the water. This requires that he retrace his steps to "Adam's Chair" and then go down a recent logging road along Upper Jane Falls until he comes back to the confluence where the water from Connie Falls will join him from his right. Retracing his steps to the top of William's Woods, he will then go on one more loop on his way back.]

For this loop he must desert the flowing water briefly and go down to the natural watercourse in the hollow to the east and his left. There he will come to Grampa Jim Dam. The location for this pris d’eau was established by Antonson's father Cortlyn and himself with the help of a builder's transit. They began with a location approximately one foot higher than the elevation of the saddle on the mountain side of the Crown and from there "surveyed" northeast until they came to the natural water course. Antonson then diverted water and by the usual method of digging enough to allow water to flow into the ditch but not out (described more completely in The Meadow Book) he continued until he had brought the water to just above the saddle. There he allowed the water to make the small fall to the saddle. This fall he named Minnie Falls after Camp’s wife (Antonson's grandmother) Minnie Martha Nancy Bottenhorn Camp. Digging through the woods as opposed to through pasture while maintaining a perfect contour was very difficult and required not only the use of a shovel but also a maddock. Antonson estimated that it took him about 40 man hours of work before the water reached the saddle. At Minnie Falls the water joins that water issuing out of William’s Woods and then continues to ring the Crown in the tiny "moat" mentioned earlier.

Just downstream from Grampa Jim Dam along the water supply to the Crown, the water passes along the face of a low near "cliff" about 20 feet high. This route was necessary to maintain the contour. At this spot the water works of the farm is the most similar to the water works of Le Valais, Switzerland, where "bisses" are often perched – even hung in wooden troughs – along true cliff faces or even overhangs. For Americans this is very obscure knowledge, but Antonson has mangaged to assemble a considerable library on the subject in French, Italian, German, and English, and has traveled to Europe twice with the principal purpose of visiting these bisses.

As the "bisse" emerges from the cliff face, just as it turns slightly to the right (going downstream) the visitor comes to Sarah Falls, built by her son Elijah when he was very young. In fact, Antonson had everything ready for this fall of water but wanted Eli to be involved. This is one of the highest drops of water on the farm and will some time be developed into a waterwheel site. Until then Sarah Falls will continue to act as a shutoff of water flowing to the Crown. The water falls to Brian Dam – also built by Eli.

Following the bisse, when the hiker arrives at the saddle north of the Crown, he has the choice of returning straight to the western "parking-lot-pasture" or leaving the water and heading down the hill to the east, his left. There he can visit Jeff Dam and follow its water, and a vehicular lane just above it, to Jill Falls very near the Cherry Tree House. As he does this, the hiker will be passing a terraced and irrigated pasture below him and a strip purposefully kept nearly wild on his right. Within this "wild" strip as the hiker nears the Cherry Tree House he will see a beginning hedge of staghorn sumac planted on an approximate contour by Antonson at Barbara Camp Antonson’s request.

At Jill Falls the hiker could walk directly past the Cherry Tree House between it and an overgrown hedge of juniper or he could turn to his left and go down a "cow stair" to the site of a vegetable garden. This site is noteworthy because it is at one of the most complicated intersections of passageways on the entire farm. There, at different times in the farm's history, at least three roads and a railroad passed in different ways. The footprints of the passageways were so intiricate that to reveal them Antonson first put the area under a covering of old rugs for one season to kill back the sod. Then he used the contour trenching method to reveal the various slight slopes made by the area’s use. Eventually when the passageways were carried back away from the spot it was possible to establish their likely "tranjectories" through the area. The resulting "garden" is a complex network of curved rows.

As part of the complex at the natural water course there appears to have been one or more buildings – almost in the course itself. As of the time of this writing this part of the complex has not yet been revealed. When Antonson came to the farm to live permanently there was a wooden bridge at this spot. After its being washed away several time and his replacing it, Antonson eventually had limestone dumped into the creek to make a ford. At that spot he intends to build Adam Dam, but only after revealing as much of the original stonework there as possible. Part of the complexity of this site is the passage of an old railway bed to its east and a strong, but seasonal spring also to its east.

Well, a short, level walk to the west along Camp Ranch Lane will take the hiker past Barbi Falls, the long greenhouse, the parterre, the pond, the wide stair, the Swiss House, the small-animal barn, back to the Plaza, and thence to the parking lots and gate.

A POSTCRIPT

This has been hurriedly written and is in no way complete or even thoroughly edited. However, it is a start.

The way to approach the Old Ways Museum [henceforth OWM] which would be most in keeping with the intent of the museum would be on foot, or in descending order of preference by horseback, carriage, bicycle, bus, car, or – least desirable because of invasion of noise to the space – motorcycle. Regardless of the mode of transportation, the traveler having come out of Bedford and through Dutch Corner will have first noticed as he rounded the curve at the top of Jew Hill (locally called that in yesteryears because of the "dynasty" of the Oppenheimers – more about which later) the view of the n

The way to approach the Old Ways Museum [henceforth OWM] which would be most in keeping with the intent of the museum would be on foot, or in descending order of preference by horseback, carriage, bicycle, bus, car, or – least desirable because of invasion of noise to the space – motorcycle. Regardless of the mode of transportation, the traveler having come out of Bedford and through Dutch Corner will have first noticed as he rounded the curve at the top of Jew Hill (locally called that in yesteryears because of the "dynasty" of the Oppenheimers – more about which later) the view of the n arrow valley below between said hill and Brumbaugh Mountain to the North. This view is gradually becoming obscured – especially in the summer – by the growth of trees on the side of the hill. That obscurity is welcomed because it gradually builds on to the division between the modern world and the "campus" of the OWM and contributes to a sort of Brigadoon or Shangri-la effect to the hollow. Second after the view a traveler will have noticed the Crown, an unfinished replica of the Elizabethan Rose Theater at the summit of the hill behind the Cherry Tree House. This Cherry Tree House will have been noticed nearly as quickly. It is a very large Pennsylvania farm house and Barbara Camp Antonson’s ancestral home – built by her great grandfather in 1863 outside of Cherry Tree, Pennsylvania, but disassembled at Barbara and Cortlyn’s expense by their son Frank Antonson, moved the 70 miles, and reassembled at the present site starting in 1983 (and continuing). The Cherry Tree House is not part of the OWM, but has a story of its own.

arrow valley below between said hill and Brumbaugh Mountain to the North. This view is gradually becoming obscured – especially in the summer – by the growth of trees on the side of the hill. That obscurity is welcomed because it gradually builds on to the division between the modern world and the "campus" of the OWM and contributes to a sort of Brigadoon or Shangri-la effect to the hollow. Second after the view a traveler will have noticed the Crown, an unfinished replica of the Elizabethan Rose Theater at the summit of the hill behind the Cherry Tree House. This Cherry Tree House will have been noticed nearly as quickly. It is a very large Pennsylvania farm house and Barbara Camp Antonson’s ancestral home – built by her great grandfather in 1863 outside of Cherry Tree, Pennsylvania, but disassembled at Barbara and Cortlyn’s expense by their son Frank Antonson, moved the 70 miles, and reassembled at the present site starting in 1983 (and continuing). The Cherry Tree House is not part of the OWM, but has a story of its own. Having descended the hill the traveler turns right into the OWM. If he is observant he will notice that this entrance is a single lane, unpaved, and with a grassy strip in the middle. Even before the gate the traveler has passed old ways of doing things in that there is a basket willow hedge separating the OWM from the road and a filtering ponds on the visitor’s right. At the gate the visitor should notice that water is flowing under a pair of tire-width low arches. This water is flowing to the visitor’s left in a leat or headrace toward the lowest of the various waterwheels on the north side of the road – the waterwheel at Nina Falls.

Having descended the hill the traveler turns right into the OWM. If he is observant he will notice that this entrance is a single lane, unpaved, and with a grassy strip in the middle. Even before the gate the traveler has passed old ways of doing things in that there is a basket willow hedge separating the OWM from the road and a filtering ponds on the visitor’s right. At the gate the visitor should notice that water is flowing under a pair of tire-width low arches. This water is flowing to the visitor’s left in a leat or headrace toward the lowest of the various waterwheels on the north side of the road – the waterwheel at Nina Falls. nder a pair of tire-width low arches. This water, however, is flowing to the visitor’s right. It is on its way to join water coming from Cort Dam in Oppenheimer run and from the tailrace of the overshot waterwheel at Jane Falls to then pass under an undershot water wheel at Elizabeth Falls beside a small springhouse-dairy-brewery before becoming the selfsame water that the visitor first noticed passing to his left under the lane.

nder a pair of tire-width low arches. This water, however, is flowing to the visitor’s right. It is on its way to join water coming from Cort Dam in Oppenheimer run and from the tailrace of the overshot waterwheel at Jane Falls to then pass under an undershot water wheel at Elizabeth Falls beside a small springhouse-dairy-brewery before becoming the selfsame water that the visitor first noticed passing to his left under the lane. Slightly behind that shop is another small building housing a flat-belt driven four siding planer. This is a machine dating from about 1890 and given to the OWM by Joseph Elyard. To the left of the lane and up a short grade is a larger building housing a flat-belt driven sawmill. This mill dates from about the 1890's and was initially driven by a steam engine. It was manufactured by the Farquahar Company and had an unusual friction disc drive for the carriage. The track of the sawmill is 50 long. Its history is that Frank Antonson bought it from Ralph Kegg in 1974, who had bought it from Harve Imler, presumably the first owner who operated in a little downstream from Imlertown. As of 2006 at least two people that attend Messiah Lutheran Church can remember the mill being run by steam. Both of the machines, the planer and the sawmill, of course have Babbitt bearings. The sawmill includes a swing saw and a sawdust drag. The machines will have to be run by a tractor’s power take off or some other gasoline e

Slightly behind that shop is another small building housing a flat-belt driven four siding planer. This is a machine dating from about 1890 and given to the OWM by Joseph Elyard. To the left of the lane and up a short grade is a larger building housing a flat-belt driven sawmill. This mill dates from about the 1890's and was initially driven by a steam engine. It was manufactured by the Farquahar Company and had an unusual friction disc drive for the carriage. The track of the sawmill is 50 long. Its history is that Frank Antonson bought it from Ralph Kegg in 1974, who had bought it from Harve Imler, presumably the first owner who operated in a little downstream from Imlertown. As of 2006 at least two people that attend Messiah Lutheran Church can remember the mill being run by steam. Both of the machines, the planer and the sawmill, of course have Babbitt bearings. The sawmill includes a swing saw and a sawdust drag. The machines will have to be run by a tractor’s power take off or some other gasoline e ngine until such a time as something older could be used. It is Antonson’s intent to eventually power them either by wood gas (a technology of the early 20th century) or methane engines. The rest of the machinery in the OWM is meant to be powered by waterpower. (The buildings for these two mills are under construction).

ngine until such a time as something older could be used. It is Antonson’s intent to eventually power them either by wood gas (a technology of the early 20th century) or methane engines. The rest of the machinery in the OWM is meant to be powered by waterpower. (The buildings for these two mills are under construction). are the "wagon shed" now a small animal barn and a "wellhead-rootcellar-oneroomschoolhouse-dovecote." This latter building’s original intent was to cover a dug well that had been filled in but continued to issue water in the wet season. Antonson re-dug that well and repaired its sandstone rubble lining. At that time he also drained it at a certain level so that water would not come out of the top and added a root cellar to it. More about this building later, but for now it might be said that the top of that original dug well is barely visible in the Schnably photograph.

are the "wagon shed" now a small animal barn and a "wellhead-rootcellar-oneroomschoolhouse-dovecote." This latter building’s original intent was to cover a dug well that had been filled in but continued to issue water in the wet season. Antonson re-dug that well and repaired its sandstone rubble lining. At that time he also drained it at a certain level so that water would not come out of the top and added a root cellar to it. More about this building later, but for now it might be said that the top of that original dug well is barely visible in the Schnably photograph.  l that uses for its fall the apparent remains of an old barn foundation – this location, however, is only revealing itself slowly. This falls is called Sister Jane Falls. Just behind it is Lyn Falls. Then the sawmill earlier mentioned is passed on the left and the planning mill on the right. Arriving at the level "plaza" if the visitor turns to his right he can go in the lower "horse" barn that houses most of the collection of artifacts. In this plaza there is evidence of prior buildings that were not laid out on the same axis that the Schnably buildings and Camp’s buildings are. This is also true of the springhouse below in the meadow at Elizabeth Falls. Their layout probably indicates a date earlier than the Schnablys. Going in the barn door, the visitor might be struck by the beauty of the gambrel-roofed plank barn construction. It allows for a barn floor completely free of posts, since the structure is held up by six pairs of opposed high-arching trusses that rest on the foundation walls.

l that uses for its fall the apparent remains of an old barn foundation – this location, however, is only revealing itself slowly. This falls is called Sister Jane Falls. Just behind it is Lyn Falls. Then the sawmill earlier mentioned is passed on the left and the planning mill on the right. Arriving at the level "plaza" if the visitor turns to his right he can go in the lower "horse" barn that houses most of the collection of artifacts. In this plaza there is evidence of prior buildings that were not laid out on the same axis that the Schnably buildings and Camp’s buildings are. This is also true of the springhouse below in the meadow at Elizabeth Falls. Their layout probably indicates a date earlier than the Schnablys. Going in the barn door, the visitor might be struck by the beauty of the gambrel-roofed plank barn construction. It allows for a barn floor completely free of posts, since the structure is held up by six pairs of opposed high-arching trusses that rest on the foundation walls. The restrooms for the OWM are essentially two-storey outhouses, which are reached from the inside of the "horse barn" on the side away from the door. (Barbara Camp Antonson used to say that a two-storey outhouse was built into the Schnably house by the time that Camp had bought it.) The waste is delivered straight into a biodigester to which is also added the horse manure and sawdust from the stables below. This biodigester produces gas to power the planning mill earlier mentioned.

The restrooms for the OWM are essentially two-storey outhouses, which are reached from the inside of the "horse barn" on the side away from the door. (Barbara Camp Antonson used to say that a two-storey outhouse was built into the Schnably house by the time that Camp had bought it.) The waste is delivered straight into a biodigester to which is also added the horse manure and sawdust from the stables below. This biodigester produces gas to power the planning mill earlier mentioned.  o contain one to three 275-gallon oval tanks. These are used for the making of charcoal in quantity. Also in this foundation along the eastern wall is the waterwheel at Jess Falls. This low volume waterwheel powers a light blast of air to the forge or the fan for drawing off fly ash from the screening process. Ultimately the floor of this foundation should never freeze even though it is, when not tented, open to the sky because along the floor runs water – not only

o contain one to three 275-gallon oval tanks. These are used for the making of charcoal in quantity. Also in this foundation along the eastern wall is the waterwheel at Jess Falls. This low volume waterwheel powers a light blast of air to the forge or the fan for drawing off fly ash from the screening process. Ultimately the floor of this foundation should never freeze even though it is, when not tented, open to the sky because along the floor runs water – not only from Jess Falls, but more importantly, from the pond on its way to Jane Falls. This latter headrace comes out of the pond as if it were from a spring house and does not freeze in winter.

from Jess Falls, but more importantly, from the pond on its way to Jane Falls. This latter headrace comes out of the pond as if it were from a spring house and does not freeze in winter.  The main artifact of this mill at Jane Falls is on the wooden floor above the wheel. There is centered a flat-belt driven predecessor to what one might now call a "Shop Master". It appears to be one-of-a-kind, and is built up out of channel steel welded together. Meant to be driven by a flat belt from a tractor, the pulleys and cone pulleys underneath its deck drive five cutting heads – a band saw, a morticer (or drill press), a ripping saw, a cut off saw, and a jointer. It is on wooden skids and was once meant to be pulled around to its place of work. Also included in the Mill at Jane Falls is a collection of flat-belt pulleys, large v-belt pulleys, shafts, couplings, bearing hangers and other components to a line shaft system.

The main artifact of this mill at Jane Falls is on the wooden floor above the wheel. There is centered a flat-belt driven predecessor to what one might now call a "Shop Master". It appears to be one-of-a-kind, and is built up out of channel steel welded together. Meant to be driven by a flat belt from a tractor, the pulleys and cone pulleys underneath its deck drive five cutting heads – a band saw, a morticer (or drill press), a ripping saw, a cut off saw, and a jointer. It is on wooden skids and was once meant to be pulled around to its place of work. Also included in the Mill at Jane Falls is a collection of flat-belt pulleys, large v-belt pulleys, shafts, couplings, bearing hangers and other components to a line shaft system.  Walking along the north side of the pond the visitor will see to his left the front of the Cherry Tree House with its juniper-covered bank below it and a long greenhouse just below that. This green house covers part of the water supply approaching Jess Falls. The rest of the supply for Jess Falls comes from the combined tail waters of Barbi Falls and Waterwheel – the highest of the OWM – and the water diverted by Adam Dam where a lane crosses the natural run. Between the long narrow "greenhouse" and the pond is a lane – almost on a contour line – and a terraced pasture which is gradually being converted into a parterre. Around the curve of the hill to the East of the Cherry Tree House is an area of terraced gardens and pasture below the leat bringing water from Jeff Dam to Barbi Falls. Rounding the upstream, eastern end of the pond involves crossing a wooden bridge then passing another of the waterwheels of the OWM. As the visitor crosses that bridge he can see to his left in a small wetlands and example of a dawn redwood. This is one of two in the OWM. What is so special about this tree is that it was thought to have been extinct and was only known through fossil evidence until one was found in China. Since then it has been introduced around the world. It is a fast-growing deciduous conifer. (This dawn redwood is just one example of Barbara Antonson's love of landscape architecture,which she tried to express on the Camp Ranch. There are many trees that have been planted in memory of someone – and a few other unusual specimens. But that subject should be considered elsewhere.) There are actually two waterwheel at the eastern end of the pond. This site is called William and Helen Falls. William Falls serves as a bypass from the pond when water needs to be diverted. Helen Falls, the other side of it allows the water to fall into the pond -- water delivered from Sven Dam (on Oppenheimer Run) and Frank Dam (on the unnamed creek that most closely feeds the pond)

Walking along the north side of the pond the visitor will see to his left the front of the Cherry Tree House with its juniper-covered bank below it and a long greenhouse just below that. This green house covers part of the water supply approaching Jess Falls. The rest of the supply for Jess Falls comes from the combined tail waters of Barbi Falls and Waterwheel – the highest of the OWM – and the water diverted by Adam Dam where a lane crosses the natural run. Between the long narrow "greenhouse" and the pond is a lane – almost on a contour line – and a terraced pasture which is gradually being converted into a parterre. Around the curve of the hill to the East of the Cherry Tree House is an area of terraced gardens and pasture below the leat bringing water from Jeff Dam to Barbi Falls. Rounding the upstream, eastern end of the pond involves crossing a wooden bridge then passing another of the waterwheels of the OWM. As the visitor crosses that bridge he can see to his left in a small wetlands and example of a dawn redwood. This is one of two in the OWM. What is so special about this tree is that it was thought to have been extinct and was only known through fossil evidence until one was found in China. Since then it has been introduced around the world. It is a fast-growing deciduous conifer. (This dawn redwood is just one example of Barbara Antonson's love of landscape architecture,which she tried to express on the Camp Ranch. There are many trees that have been planted in memory of someone – and a few other unusual specimens. But that subject should be considered elsewhere.) There are actually two waterwheel at the eastern end of the pond. This site is called William and Helen Falls. William Falls serves as a bypass from the pond when water needs to be diverted. Helen Falls, the other side of it allows the water to fall into the pond -- water delivered from Sven Dam (on Oppenheimer Run) and Frank Dam (on the unnamed creek that most closely feeds the pond)